WARREN M. ANDERSON, the chairman of the Union Carbide Corporation, has not taken his wife Lillian out to dinner much in the past five months. "I kind of felt that if somebody caught me laughing over in the corner over something," he said, "they might not think it was appropriate."

|

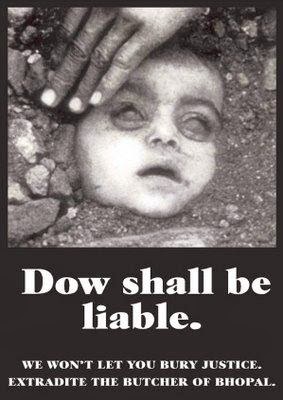

Warren M. Anderson (November 29, 1921 – September 29, 2014) Chairman and CEO, Union Carbide Corporation at the time of the Bhopal disaster in 1984 |

To be sure, since Dec. 3, 1984 when a chemical accident at a Union Carbide plant killed more than 2,000 people and injured thousands more in Bhopal, India, the 63-year-old Mr. Anderson has not felt much like laughing anyway. "It must be like when someone loses a son or a daughter," he said. "You wake up in the morning thinking, can it possibly have occurred? And then you know it has and you know it's something you're going to have to struggle with for a long time." The public ordeal of the Union Carbide Corporation since the Bhopal tragedy has been well-chronicled. The huge chemical concern has seen its stock plummet, its financial health challenged by multibillion-dollar lawsuits and the pace of its strategic acquisitions slow due to problems in raising cash.

But obscured amid the corporate concerns has been the personal trauma of the one man who bears ultimate responsibility for his corporation's actions. He would willingly avoid the aftermaths of that reponsibility, but cannot.

In fact, he offered to resign in return for "a golden handshake" - a lucrative severance package - but was turned down. He recalls one board member saying, "You got us into this, you've got to hang around and get us out." A picture of the toll that the trauma is taking emerged during an unusually candid 6 1/2-hour conversation spread over two days in Mr. Anderson's simply furnished office at Union Carbide's headquarters in Danbury, Conn. And it was reinforced by a two-hour talk with Lillian Anderson, a soft-spoken former schoolteacher who had never been previously interviewed by a reporter, in the living room of their Greenwich, Conn., home, overlooking a small garden of geraniums, azaleas and other flowers that she had planted.

The discussions provided a glimpse of how an unprecedented corporate crisis looks from the inside and of how a huge company coped with a disaster in the first days after it hit. They revealed a formerly low-profile chief executive who suddenly must balance the conflicting demands of stockholders, company attorneys, reporters, employees, Congressmen, foreign government officials and other constituencies, all in the glare of the public eye.

|

| Bhopal gas tragedy survivors share sweets after Warren Anderson’s death, in Bhopal on Friday. (HT photo) |

Even before the accident, the Andersons were a shy couple, living modestly despite his nearly $1 million annual compensation. Their attached three-bedroom townhouse is simply furnished, the neighborhood not particularly exclusive. The couple, who have no children, spend a lot of time together, working in their garden, fishing and doing their own renovation of a small house in eastern Long Island. He reads mysteries; she fixes dinner.

"We've never been into keeping up with the Joneses," Mrs. Anderson said. "We'd rather have a small garden that we did ourselves than a large garden done by hired landscapers."

But these days, that quiet life style verges on reclusiveness. Tired of continual questions and comments, they stay home even more than before. They take long walks in the evenings to unwind and talk. She has been, and still is, his only real confidante, "the only one who tells me things the way they really are," he said. And often, said Mrs. Anderson, a stylish woman with straight gray hair and soft gray eyes, they retire at night "with lumps in our chests."

Mr. Anderson "always slept like a baby" before Bhopal, she said. Since then, they both have had trouble sleeping. Mr. Anderson has a lot to think about during those troubled nights. "I feel like I'm taking tests all the time," the white-haired executive said. "You know there is going to be a grade on everything you do and everything you say."

Although he still insists that the Indian Government is partly to blame for allowing people to live so close to the Carbide pesticide plant in Bhopal, he has since March publicly admitted that the plant itself had violated company operating standards and used procedures that would not be tolerated in the United States. He says that Carbide must shoulder much of the responsibility for the accident, and that doing so requires more than public displays of sorrow. "Flying a flag at half mast may make you feel a little better, but it doesn't get rid of the problem," he said.

Thus, Mr. Anderson is firm about the need to pay a substantial settlement to the survivors of those killed in Bhopal, as well as to an estimated 200,000 injured. Whether his definition of "substantial" meshes with his critics' definition of "adequate" is unknown for now, however. The Indian Government reportedly has rejected a $200 million Carbide offer as a permanent settlement. Carbide also has offered $7 million in "interim relief," of which the Indian Government has accepted $1 million. And the company sent medical supplies to Bhopal in the days following the accident.

Meanwhile, Mr. Anderson's pre-Bhopal plans for Carbide, the nation's third-largest chemical producer behind Du Pont and Dow, have slowed measurably.

The company's stock, which was $74 a share in 1982 and about $50 before the accident, is now at $38. That depressed stock price, combined with the need to conserve cash due to legal claims against the company, has prevented Mr. Anderson from aggressively pursuing the acquisition policy he had adopted. "Those kinds of things are almost impossible to do as long as you have Bhopal hanging over your head," he said.

There were disappointments of a more common sort well before Bhopal. Company officials in 1979, when Mr. Anderson was president, predicted that 1983 sales would reach $13 billion. In fact, sales reached only $9 billion and earnings dropped more than 90 percent, from a peak of $13.36 a share in 1980 to $1.13 a share in 1983. Earnings recovered to $4.59 a share in 1984, but some analysts are unimpressed.

"From an investment and earnings viewpoint, Union Carbide has been a disappointment coming out of the recession," said James M. Arenson, vice president of Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette, which removed Carbide from its recommended list last September. "They were slower in cutting back costs and late in taking some write-offs."

In fact, Mr. Arenson and several other observers contend that investors, unlike the general public, will remember Mr. Anderson more for the company's rather mediocre performance than for his handling of the Bhopal tragedy. "What he did on Bhopal won't have any material effect on his ability to achieve better financial performance," said Richard Kossoff, president of R.M. Kossoff & Associates, Inc., chemical industry consultants.

At the time of the accident Union Carbide was struggling to change its focus. It had - ironically, in light of Bhopal - finally shaken off the reputation as a polluter that had dogged it in the early 1970's, and was getting high marks from ecologists.

The company was ready to devote full attention to the business of business.

Specifically, Mr. Anderson, who became chairman in 1982, wanted to reduce the company's reliance on commodity chemicals and increase its emphasis on areas such as consumer products, thus supplementing its mainstays of Glad bags, Prestone antifreeze and Eveready batteries.

Carbide had been making progress toward some of its goals. It has greatly increased efficiency, for example. Between 1979 and 1984, the number of employees dropped to 98,366 from 117,031, even though sales rose to $9.5 billion from $9.2 billion. Revenue per employee rose 22.9 percent, to $96,578 from $78,611.

The company has also made a few acquisitions since Bhopal, despite its financing problems. It acquired STP oil, expanded its industrial gas business and become involved in enhanced oil recovery. Earnings per share are still inching up; William R. Young of Dean Witter Reynolds expects them to rise 20 percent this year, to $5.50, even with Bhopal hanging over the company. In fact, some fairly savvy outsiders have demonstrated renewed faith in Carbide's future. An investor group led by the Bass Brothers of Texas has bought about 5 percent of Carbide's stock since the accident.

Within the industry and the company, Mr. Anderson has been trying mightily to maintain at least a semblance of business normalcy. He has for years breakfasted every morning in the company cafeteria, chatting with workers over a roll and coffee. These days, he uses those breakfast chats to sense whether employees are reacting badly to Bhopal. "He has great sensitivity to what's pulling on people, the stresses that other people feel," said Ronald S. Wishart, Carbide's vice president of government relations and a colleague of Mr. Anderson's for 25 years. And, Mr. Wishart said, Mr. Anderson takes personal responsibility for alleviating their distress. W ARREN MARTIN ANDERSON learned about responsibility early. The son of a carpenter who emigrated from Sweden, he used to help his father install floors and later delivered newspapers in his Bay Ridge neighborhood for the defunct Brooklyn Eagle. He is the middle of three children.

At 6-foot 2 and 210 pounds, and with a perfect score on math exams, he won both football and academic scholarships to Colgate. At first he wanted to be a physician but "my parents didn't have any money" to put him through more years of schooling. So he majored in chemistry.

After graduation in 1942 he enlisted in the Navy and trained to be a fighter pilot, but never saw combat. He was discharged when the war ended in 1945. In the Navy he played end on a football team that had the legendary Bear Bryant as a coach and as quarterback had Otto Graham, who went on to be one of the best professional players in the history of the game. "I still keep in touch with him," Mr. Anderson said.

After the Navy, Mr. Anderson made the rounds of chemical companies in New York and took the first job offered him - by Union Carbide. In the next few years he added two more skills that were to serve him well. During a stint as a salesman, he learned the importance of marketing, and of keeping attuned to customer needs. And at night, he went for a law degree at Indiana University.

That law degree is helping a lot in dealing with company lawyers now. "They know I'm a lawyer," he said. "They can't get away with the answer, 'No, you can't do that.' They have to say what the problem is. I can talk their language."

He rose steadily at Carbide, averaging two to three years per position, through general sales manager in New York, vice president of the international division, president of the chemicals and plastics group and president and chief operating officer in 1977. He now presides over a company with 700 plants in more than three dozen countries.

Until recently, Mr. Anderson had managed to keep a fairly low profile. His office sports a paperweight inscribed with his favorite Chinese proverb: "Leader is best when people barely know he exists."

So it was, in his words, "quite a shock" to be suddenly thrust into world prominence by an unanticipated and enormous tragedy. M R. and Mrs. Anderson remember the hours surrounding Bhopal vividly.

The night before the accident, they and some friends attended an awards ceremony at the Kennedy Center in Washington. Mr. Anderson had a bad cold and was about to fly home to bed on Monday morning, Dec. 3, when the phone rang at about 8 A.M. Alec Flamm, Union Carbide's president, said there had been an accident at the Bhopal plant and that there were deaths, but no more details were available.

A few hours later, Mr. Anderson was back in Greenwich and Mr. Flamm was calling him again. By then 18 hours had passed since a cloud of toxic methyl isocyanate, a pesticide ingredient, had drifted over Bhopal, and hundreds of people had fallen dead on Bhopal's streets. But because of the difficulty of getting information from India to the United States -overbooked planes, overloaded telex lines, far too few telephone connections - Mr. Flamm's most recent information from India was that 60 people had died.

It is with bitter irony that Mr. Anderson recalls his reaction to that number of deaths. "I couldn't comprehend it," he said. "We thought it couldn't be that bad, that when the next call comes through it will be better, not worse."

Mr. Anderson fielded calls from his bed all day Monday; his wife listened to the news on the radio in the living room. "We had this frustrating problem of being able to see on television what was going on in Bhopal and unable to get a line through to find anything directly ourselves," he said.

A management team, made up of Mr. Flamm and the six executive vice presidents of the company's divisions, assembled in Danbury to direct communications and to marshall the company's resources to deal with the crisis.

Mr. Anderson, meanwhile, decided immediately that he, as well as a technical and medical team, would go to India. "I sort of felt that if I were over there I could make judgments and decisions on the spot," he said. Mrs. Anderson remembers her husband's trip to India as among the most fearful times of her life. "I was afraid for him stepping off the plane in Bhopal," she said. "It was all so public." Indeed, in some ways Mrs. Anderson's burden was heavier than Mr. Anderson's in those early days after Bhopal. Rather than share with others her fear that he might come to harm in India, Mrs. Anderson kept her own counsel. "I wanted to prepare myself for the worst, where I might be alone," she said. Even after he returned, her fears for Mr. Anderson's health were a constant companion. She put a doctor secretly on call in case he suddenly collapsed from the stress. Yet through it all, while serving as a sounding board for Mr. Anderson's worries and frustrations, she has kept quiet about her own. "I didn't want him to worry about the fact that I was worried," she said. On Tuesday, Dec. 4, Mr. Anderson boarded a plane for Bombay, where he met with Keshub Mahindra, board chairman of Union Carbide India Ltd., and its managing director, V.P. Gokhale. The three decided to go to Bhopal, survey the situation, meet with Arjun Singh, the chief minister of the state of Madhya Pradesh, and offer interim relief and a permanent damage settlement. "We were talking about generous numbers, by anybody's standards," Mr. Anderson said.

The three were arrested as they stepped off the plane in Bhopal. Mr. Anderson was detained for several hours and then flown back to New Delhi; the other two were put under a form of house arrest at Union Carbide's guest house in Bhopal for nine days. In New Delhi he met with American and Indian officials, but little progress was made toward a settlement.

As it turned out, Mrs. Anderson's worries were unfounded. Mr. Anderson said that no one threatened him during the five days he was in India - although the fear was sometimes there. "When trucks go over bumps and big noises occur outside in the middle of the night, you sort of jump a couple of feet and you sort of settle back down again," he said.

It was when he got back to Connecticut that the true harassment started. Although there was no hate mail - a silence that Mr. Anderson found "amazing" - there was constant hounding by reporters, advice givers, attorneys, stockholders and consultants offering their services. He hid out with his wife for a week in a Stamford hotel, taking along her 84-year-old mother from Brooklyn for company. They had all their meals sent up. This was the low point, he said, "a grown man hiding in a hotel room." Things have calmed down since then. The two spent this weekend in their Bridgehampton, L.I., house, the first time since the accident. "I've learned to make every day count," Mrs. Anderson said.

Things are calmer on the business front, too. Executives of other chemical companies have rallied around Carbide and Mr. Anderson, giving him at least a semblance of a support structure.

"At hearings and at meetings that I've been to, there have been other members of the chemical industry there too, stating their piece or giving their testimony," he said. "It has been helpful that other people have taken on some burdens."

But Mr. Anderson is still struggling with how to balance the demands of differing constituencies. ''If you listen to your lawyers you would lock yourself up in a room someplace,'' he said. ''If you listen to the public relations people they would have you answer everything. I would be on every TV program.'' There are demands from shareholders, retirees, insurance companies, government officials. He says he constantly risks satisfying one group while upsetting another.

Perhaps the group he worries about most is Union Carbide's own employees. ''There are a lot of Carbide people who bear the stigma of Bhopal even though they have no relationship with it whatsoever,'' he said.

This past winter, Mr. Anderson made a series of morale-boosting videotapes to be distributed to corporate locations around the world. ''We have a lot to prove and the world is watching,'' he said on one of the tapes. But he quickly added, ''What I have seen so far gives me enormous confidence that Carbiders will meet the test.''

He is constantly looking for at least some identifiable good to be derived from the tragedy of Bhopal.

He notes, in fact, that employees have pulled together. ''It is very much like a family where when there is a problem you close ranks,'' he said. And he notes that there is an opportunity to learn a wide variety of lessons from the accident, for Carbide specifically and for all multinational companies in general. One is that overseas plants must be inspected more frequently. Another is that overseas managers, both natives of the foreign country as well as expatriate Americans, should be more familiar with the operations they head - a particularly important consideration for Carbide, which is organized on a geographical basis, not a product line basis. Executives both here and overseas are not always expert in technologies they manage. The head of Union Carbide India Ltd., Mr. Gokhale, came from Carbide's battery division in India, and admittedly was not particularly familiar with the Bhopal pesticide plant's processes. Some former company officials contend that the unfamiliarity enabled problems to fester.

Another lesson, Mr. Anderson said, is that extra thought must be given to locating hazardous chemical processes in some areas of third world countries, and to negotiating better control of those facilities with the host governments. ''I think everybody is going to seriously question the degree of control that you have,'' he said. American companies, he believes, will demand more control than they have now, including the right to do safety audits at any time. The alternative, he said, should be that ''you just will not make that investment.''

Mr. Anderson will turn 65 on Nov. 29, 1986, so he has about 18 months to put the lessons he has learned into effect before he retires. But if litigation drags on, he warns, the constructive aspects of Bhopal will take a back seat to the rancor.

''Maybe I wish to be remembered for resolving an issue like Bhopal,'' he said. ''Not many people have the chance to be in the middle of a mess like this one and come out of it. So, if you can come out in a positive way, look back on it and say, yes, I know it was a terrible tragedy, but some benefits accrued, and here's what they are - that's not bad.''

THE PSYCHOLOGICAL VIEW

Eminent psychologists say that, perhaps more than anything else, Warren M. Anderson's ability to talk about Bhopal and to accept the magnitude of the tragedy indicates an unusually healthy and constructive manner of dealing with his own reactions.

¶ ''To be able to talk about it is healthy; to be able to talk about it with one's wife is healthier still; to talk about it with one's wife while walking to discharge tensions is very, very healthy,'' said Harry Levinson, a professor of psychology at the Harvard Medical School and an expert on executive stress.

"If you pretend everything is normal, you have a poor grieving process, and you will not get back into the realities of everyday life very quickly," added John R. Sauer, an industrial psychologist for consultants Rohrer, Hibler & Replogle Inc.

Too much defensiveness, he warns, results in "guilt, anxiety and embarrassment."

Mr. Anderson's occasional sleeplessness is not much to worry over, psychologists say. But they expect that executives at other companies who have denied that serious problems existed or blamed others for them will have longer bouts of unease than will Mr. Anderson.

Mr. Levinson notes that Ford Motor Company was initially reluctant to admit how bad the problems with the Pinto's exploding gasoline tanks were, while the General Motors Corporation responded to consumer advocate Ralph Nader's discovery of safety problems with the Corvair by initiating a personal attack against Mr. Nader. Mr. Levinson's guess is that top executives at both companies probably suffered a good deal of psychological trauma by not dealing fully with disasters. He says that feelings of guilt or blame may fester and hamper performance for years.

By contrast, he predicts that all parties at Johnson & Johnson will remain psychologically unscathed, even though tainted Tylenol capsules killed seven people in Chicago. The company reacted quickly, removing Tylenol from store shelves and almost immediately initiating packaging changes that would make undetected tampering almost impossible.

The disaster that Mr. Anderson must deal with, however, differs from these examples in several respects. Victims numbered in the thousands, making the basis for guilt much greater. And dealing in a foreign culture and with a foreign government added greatly to the frustration. ''Senior managers like to be in control,'' Mr. Sauer said. Because in many ways Mr. Anderson felt helpless, the crisis ''was especially complex and difficult'' to deal with, Mr. Sauer said.

But the distance factor had a plus side for Mr. Anderson: He did not personally view the worst of carnage. And that, says Norman R. Bernstein, a psychiatrist at the University of Chicago and an authority on stress consulted often by attorneys in legal actions involving the subject, probably helped Mr. Anderson cope with the enormity of Bhopal. Dr. Bernstein said studies show that soldiers who drop bombs from miles in the air suffer far less post-battle stress than those who see people die close-up. ''If you don't see dead bodies, your ability to detach yourself from the tragedy is greater,'' he said.

- By STUART DIAMOND Published: May 19, 1985 in New York Times

Very informative blog on Bhopal Gas Disaster ...I was searching information regarding Bhopal Gas Disaster..Good insight on incident..

ReplyDelete